I Skipped a "Rite of Passage." What Next?

Virgins, abstinence-only sex-ed, tradwives, and more! It’s a fun time.

“Are we going to learn about birth control?” is the one question I remember asking in seventh-grade sex ed. I perkily raised my hand, ready to cause a fight. Don’t get me wrong, I was a painfully shy middle-schooler, but the feminism ran deep even then. My older sister, who had gone through the same Arizona abstinence-based sex education program only a few years prior, informed me that they don’t tell girls about birth control. Sure enough, my teacher responded with a curt “No.” End of conversation, if one can even call it that.

The unspoken theme behind my “sex education” class was one of loss — when I have sex with a man for the first time, I will inevitably lose something that was once sacred to me. There was no mention of grief, or on the other hand, celebration for this “monumental event.” The loss of one’s virginity is a grey area. It is a “rite of passage” to lose your virginity, but there is no why. Why is it such a big deal, why is it a life-altering event that I should be scared of to the point where I am abstinent from sexual activity but excited to the point where I need to do it, sooner rather than later, but “when you’re ready”?

This grey area had very specific constraints, though. I had to lose my virginity to the right man, preferably the one I would end up marrying. But wouldn’t that make me a prude? Only having ever slept with one man? Well I shouldn’t sleep with too many men, that would make me a slut, a whore. And the timing! I had to have sex for the first time at the right age — anywhere between 16-18 was acceptable, with 17 really being the sweet spot — not too young, not too old. It should be more romantic than sweaty car sex but not as choreographed as on a bed of roses with candles illuminating the room — you don’t want to come off as easy, undermining the big deal this is, and you don’t want to come off as desperate, overinflating this very human activity. There’s that elusive sweet spot — once you find it, you’re golden (ironically, it sounds like I’m describing the G-spot). This sweet spot is never verbally expressed — it’s understood through coded conversations and years of conditioning.

The Virgin Suicides, dir. Sofia Coppola. Photo by Ronald Grant

Long story short, I no longer desire sex or intimate relationships with men, not that I ever really did, but that all that pesky patriarchal conditioning still sticks in my head, despite my raging lesbianism. In my naivety, I felt that everyone had agreed that sex shouldn’t be taboo for one gender and celebrated for the other.

But along came the rise of tradwifery, a rise that quickly jolted me back into reality — a reality where patriarchy is the natural way of life and women are biologically inclined to be homemakers and a bunch of other bioessentialist and misogynistic bullshit talking points. But this time it was wrapped up in a neat little bow, with cows, milkmaid dresses, and skinny, upper-class white women. Not that it was ever wrapped up in something else, but rather that they are saying the quiet part out loud this time. “Yes, you’re right! We do want women in the kitchen and under the rule of patriarchy. Yes, we are misogynists! We do value the skinny white woman above all else!” Society defines “woman” and “womanhood” on said woman’s relation to men. The tradwife phenomenon has become so popular because the woman’s identity is based on her relationship with a man. In the title, she is defined by her status of “wife” with little else substantiating her identity. The label of “wife” automatically encapsulates all other duties wives are supposed to have — homemaking, motherhood, cooking, cleaning, the occasional milking of the cows and tending to farm life — there is no room to simply be a wife without kids, a wife who works, a wife who has a life outside of her own patriarchal prison.

Tradwifery undermines the push towards the embrace of female pleasure. Absolutely, some women find happiness and fulfillment in being mothers, making their own bread, and devoting their lives to the good of their families — that’s great, truly. However, the push of the tradwife lifestyle/aesthetic serves to advance the patriarchal narrative that that is the only righteous life for a woman to lead. Female pleasure is the antithesis of patriarchy. In this case, pleasure is not limited to orgasms and sexual fulfillment, it also applies to the basic daily pleasures that women under patriarchy are stripped of — time away from work, time for themselves, time for indulging in the things that are deemed “luxuries” but are truly simple delights that everyone should be entitled to. Yet factors like socioeconomic inequalities, gender-based violence, and the existence of systemic oppression forcefully prohibit women from experiencing these things.

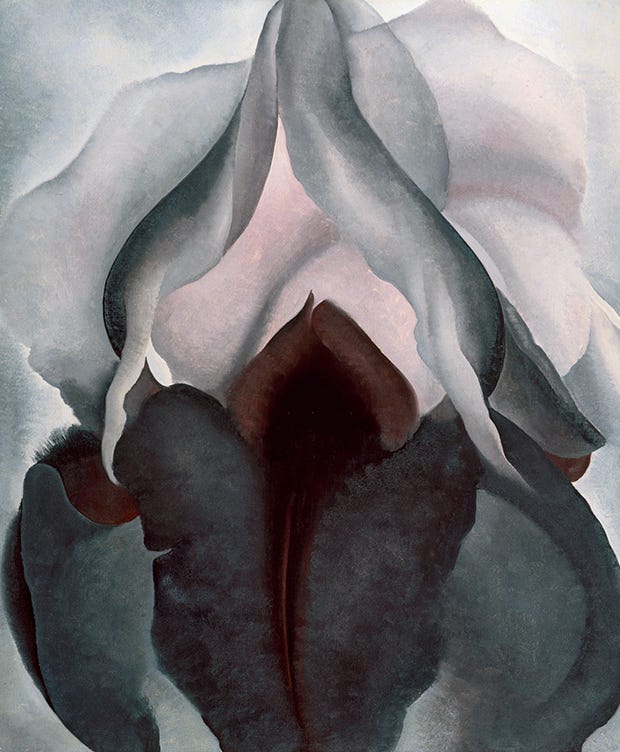

Black Iris (1926) by Georgia O’Keeffe

Because I actively try to live my life in rejection of the patriarchy, I have been forced to re-examine female pleasure and the concept of virginity — why must I lose something? I mean really, is the status of my hymen that important? It shouldn’t be, that’s for sure.

So, do I need this “rite of passage?” That begs the question — what even is a rite of passage? While the term itself is defined as “a ceremony or ritual of the passage which occurs when an individual leaves one group to enter another … (involving) a significant change of status in society,” the perpetuation of it in this context is through the strict lens of virginity and the loss of it. Surely penis-to-vagina-penetrative sex should not be the one thing my womanhood depends on. I shouldn’t have to adhere to heterosexual-cisgender sex to be deemed a woman, nor should my “graduation” from girl to woman require a singular, life-altering experience. That’s a lot of pressure to put on a girl, a child — to base your whole life on the coveted experience of losing something. Boys and men get to gain the status of someone who has had sex while girls and women lose the label of virgin — a label they are taught to hold on to until the “perfect” time (which is, of course, determined by the patriarchy).

My sexual activity should not determine my womanhood. It shouldn’t be based on how many men I sleep with, how much pink I wore as a child, or at what age I “lost my virginity” at. My womanhood — and by association, my feminist ethos — is not defined by my proximity to men and it is not defined by one thing or idea — it is a constantly evolving reflection of the way that I view and participate in the world. Furthermore and most importantly, it is shaped and defined by me, myself, and I.

Audrey you’re so talented - I absolutely devoured this piece!!

Another excellent article Audrey.